Throttle (Kindle Single) Read online

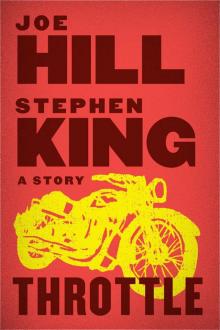

THROTTLE

A Tale Inspired by “Duel”

Joe Hill and Stephen King

Contents

Cover

Title page

Throttle

About the Authors

Credits

Copyright

More from the Authors

About the Publisher

Throttle

THEY RODE WEST FROM THE SLAUGHTER, through the painted desert, and did not stop until they were a hundred miles away. Finally, in the early afternoon, they turned in at a diner with a white stucco exterior and pumps on concrete islands out front. The overlapping thunder of their engines shook the plate-glass windows as they rolled by. They drew up together among parked long-haul trucks, on the west side of the building, and there they put down their kickstands and turned off their bikes.

Race Adamson had led them the whole way, his Harley running sometimes as much as a quarter-mile ahead of anyone else’s. It had been Race’s habit to ride out in front ever since he had returned to them, after two years in the sand. He ran so far in front it often seemed he was daring the rest of them to try and keep up, or maybe had a mind to simply leave them behind. He hadn’t wanted to stop here but Vince had forced him to. As the diner came into sight, Vince had throttled after Race, blown past him, and then shot his hand left in a gesture The Tribe knew well: follow me off the highway. The Tribe let Vince’s hand gesture call it, as they always did. Another thing for Race to dislike about him, probably. The kid had a pocketful of them.

Race was one of the first to park but the last to dismount. He stood astride his bike, slowly stripping off his leather riding gloves, glaring at the others from behind his mirrored sunglasses.

“You ought to have a talk with your boy,” Lemmy Chapman said to Vince. Lemmy nodded in Race’s direction.

“Not here,” Vince said. It could wait until they were back in Vegas. He wanted to put the road behind him. He wanted to lie down in the dark for a while, wanted some time to allow the sick knot in his stomach to abate. Maybe most of all, he wanted to shower. He hadn’t gotten any blood on him, but felt contaminated all the same, and wouldn’t be at ease in his own skin until he had washed the morning’s stink off.

He took a step in the direction of the diner, but Lemmy caught his arm before he could go any farther. “Yes. Here.”

Vince looked at the hand on his arm—Lemmy didn’t let go; Lemmy of all the men had no fear of him—then glanced toward the kid, who wasn’t really a kid at all anymore and hadn’t been for years. Race was opening the hardcase over his back tire, fishing through his gear for something.

“What’s to talk about? Clarke’s gone. So’s the money. There’s nothing left to do. Not this morning.”

“You ought to find out if Race feels the same way. You been assuming the two of you are on the same page even though these days he spends forty minutes of every hour pissed off at you. Tell you something else, boss. Race brought some of these guys in, and he got a lot of them fired up, talking about how rich they were all going to get on his deal with Clarke. He might not be the only one who needs to hear what’s next.” He glanced meaningfully at the other men. Vince noticed for the first time that they weren’t drifting on toward the diner, but hanging around by their bikes, casting looks toward him and Race both. Waiting for something to come to pass.

Vince didn’t want to talk. The thought of talk drained him. Lately, conversation with Race was like throwing a medicine ball back and forth, a lot of wearying effort, and he didn’t feel up to it, not with what they were driving away from.

He went anyway, because Lemmy was almost always right when it came to Tribe preservation. Lemmy had been riding six to Vince’s twelve going back to when they had met in the Mekong Delta and the whole world was dinky dau. They had been on the lookout for trip wires and buried mines then. Nothing much had changed in the almost forty years since.

Vince left his bike and crossed to Race, who stood between his Harley and a parked truck, an oil hauler. Race had found what he was looking for in the hardcase on the back of his bike, a flask sloshing with what looked like tea and wasn’t. He drank earlier and earlier, something else Vince didn’t like. Race had a pull, wiped his mouth, held it out to Vince. Vince shook his head.

“Tell me,” Vince said.

“If we pick up Route 6,” Race said, “we could be down in Show Low in three hours. Assuming that pussy rice-burner of yours can keep up.”

“What’s in Show Low?”

“Clarke’s sister.”

“Why would we want to see her?”

“For the money. Case you hadn’t noticed, we just got fucked out of sixty grand.”

“And you think his sister will have it.”

“Place to start.”

“Let’s talk about it back in Vegas. Look at our options there.”

“How about we look at ’em now? You see Clarke hanging up the phone when we walked in? I heard a snatch of what he was saying through the door. I think he tried to get his sister, and when he didn’t, he left a message with someone who knows her. Now why do you think he felt a pressing need to reach out and touch that toe-rag as soon as he saw all of us in the driveway?”

To say his goodbyes was Vince’s theory, but he didn’t tell Race that. “She doesn’t have anything to do with this, does she? What’s she do? She make crank too?”

“No. She’s a whore.”

“Jesus. What a family.”

“Look who’s talking,” Race said.

“What’s that mean?” Vince asked. It wasn’t the line that bothered him, with its implied insult, so much as Race’s mirrored sunglasses, which showed a reflection of Vince himself, sunburnt and a beard full gray, looking puckered, lined, and old.

Race stared down the shimmering road again and when he spoke he didn’t answer the question. “Sixty grand, up in smoke, and you can just shrug it off.”

“I didn’t shrug anything off. That’s what happened. Up in smoke.”

Race and Dean Clarke had met in Fallujah—or maybe it had been Tikrit. Clarke, a medic specializing in pain management, his treatment of choice being primo dope accompanied by generous helpings of Wyclef Jean. Race’s specialties had been driving Humvees and not getting shot. The two of them had remained friends back in The World, and Clarke had come to Race a half a year ago with the idea of setting up a meth lab in Smith Lake. He figured sixty grand would get him started, and that he’d be making more than that per month in no time.

“True glass,” that had been Clarke’s pitch. “None of that cheap green shit, just true glass.” Then he’d raised his hand above his head, indicating a monster stack of cash. “Sky’s the limit, yo?”

Yo. Vince thought now he should have pulled out the minute he heard that come out of Clarke’s mouth. The very second.

But he hadn’t. He’d even helped Race out with twenty grand of his own money, in spite of his doubts. Clarke was a slacker-looking guy who bore a passing resemblance to Kurt Cobain: long blond hair and layered shirts. He said yo, he called everyone man, he talked about how drugs broke through the oppressive power of the overmind. Whatever that meant. He surprised and charmed Race with intellectual gifts: plays by Sartre, mix tapes featuring spoken-word poetry and reggae dub.

Vince didn’t resent Clarke for being an egghead full of spiritual-revolution talk that came out in some bullshit half-breed language, part Pansy and part Ebonics. What disconcerted Vince was that when they met, Clarke already had a stinking case of meth mouth, his teeth falling out and his gums spotted. Vince didn’t mind making money off the shit but had a knee-jerk distrust of anyone gamy enough to use it.

And still he put up money, had wanted s

omething to work out for Race, especially after the way he had been run out of the army. And for a while, when Race and Clarke were hammering out the details, Vince had even half-talked himself into believing it might pay off. Race seemed, briefly, to have an air of almost cocky self-assurance, had even bought a car for his girlfriend, a used Mustang, anticipating the big return on his investment.

Only the meth lab caught fire, yo? And the whole thing burned to a shell in the space of ten minutes, the very first day of operation. The wetbacks who worked inside escaped out the windows and were standing around, burnt and sooty, when the fire trucks arrived. Now most of them were in county lockup.

Race had learned about the fire, not from Clarke, but from Bobby Stone, another friend of his from Iraq, who had driven out to Smith Lake to buy ten grand worth of the mythical true glass, but who turned around when he saw the smoke and the flashing lights. Race had tried to raise Clarke on the phone, but couldn’t get him, not that afternoon, not in the evening. By eleven, The Tribe was on the highway, headed east to find him.

They had caught Dean Clarke at his cabin in the hills, packing to go. He told them he had been just about to leave to come see Race, tell him what happened, work out a new plan. He said he was going to pay them all back. He said the money was gone now, but there were possibilities, there were contingency plans. He said he was so goddamn fucking sorry. Some of it was lies, and some of it was true, especially the part about being so god-damn fucking sorry, but none of it surprised Vince, not even when Clarke began to cry.

What surprised him—what surprised all of them—was Clarke’s girlfriend hiding in the bathroom, dressed in daisy print panties and a sweatshirt that said Corman High Varsity. All of seventeen and soaring on meth and clutching a little .22 in one hand. She was listening in when Roy Klowes asked Clarke if she was around, said that if Clarke’s bitch blew all of them, they could cross two hundred bucks off the debt right there. Roy Klowes had walked in the bathroom, taking his cock out of his pants to have a leak, but the girl had thought he was unzipping for other reasons and opened fire. Her first shot went wide and her second shot went into the ceiling, because by then Roy was whacking her with his machete, and it was all sliding down the red hole, away from reality and into the territory of bad dream.

“I’m sure he lost some of the money,” Race said. “Could be he lost as much as half what we set him up. But if you think Dean Clarke put the entire sixty grand into that one trailer, I can’t help you.”

“Maybe he did have some of it tucked away. I’m not saying you’re wrong. But I don’t see why it would wind up with the sister. Could just as easily be in a Mason jar, buried somewhere in his backyard. I’m not going to pick on some pathetic hooker for fun. If we find out she’s suddenly come into money, that’s a different story.”

“I was six months setting this deal up. And I’m not the only one with a lot riding on it.”

“Okay. Let’s talk about how to make it right in Vegas.”

“Talk isn’t going to make anything right. Riding is. His sister is in Show Low today, but when she finds out her brother and his little honey got painted all over their ranch—”

“You want to keep your voice down,” Vince said.

Lemmy watched them with his arms folded across his chest, a few feet to Vince’s left, but ready to move if he had to get between them. The others stood in groups of two and three, bristly and road dirty, wearing leather jackets or denim vests with the gang’s patch on them: a skull in an Indian headdress, above the legend The Tribe • Live on the Road, Die on the Road. They had always been The Tribe, although none of them were Indian, except for Peaches, who claimed to be half-Cherokee, except when he felt like saying he was half-Spaniard or half-Inca. Doc said he could be half-Eskimo and half-Viking if he wanted, it still added up to all retard.

“The money is gone,” Vince said to his son. “The six months too. See it.”

His son stood there, the muscles bunched in his jaw, not speaking. His knuckles white on the flask in his right hand. Looking at him now, Vince was struck with a sudden image of Race at the age of six, face just as dusty as it was now, tooling around the gravel driveway on his green Big Wheels, making revving noises down in his throat. Vince and Mary had laughed and laughed, mostly at the screwed-up look of intensity on their son’s face, the kindergarten road warrior. He couldn’t find the humor in it now, not two hours after Race had split a man’s head open with a shovel. Race had always been fast, and had been the first to catch up to Clarke when he tried to run in the confusion after the girl started shooting. Maybe he had not meant to kill him. Race had only hit him the once.

Vince opened his mouth to say something more, but there was nothing more. He turned away, started toward the diner. He had not gone three steps, though, when he heard a bottle explode behind him. He turned and saw Race had thrown the flask into the side of the oil rig, had thrown it exactly in the place Vince had been standing only five seconds before. Throwing it at Vince’s shadow maybe.

Whisky and chunks of glass dribbled down the battered oil tank. Vince glanced up at the side of the tanker and twitched involuntarily at what he saw there. There was a word stenciled on the side and for an instant Vince thought it said SLAUGHTERIN. But no. It was LAUGHLIN. What Vince knew about Freud could be summed up in less than twenty words—dainty little white beard, cigar, thought kids wanted to fuck their parents—but you didn’t need to know much psychology to recognize a guilty subconscious at work. Vince would’ve laughed if not for what he saw next.

The trucker was sitting in the cab. His hand hung out the driver’s-side window, a cigarette smoldering between two fingers. Midway up his forearm was a faded tattoo, DEATH BEFORE DISHONOR, which made him a vet, something Vince noted, in a distracted sort of way, and immediately filed away, perhaps for later consideration, perhaps not. He tried to think what the guy might’ve heard, measure the danger, figure out if there was a pressing need to haul Laughlin out of his truck and straighten him out about a thing or two.

Vince was still considering it when the semi rumbled to noisy, stinking life. Laughlin pitched his ciggie into the parking lot and released his air brakes. The stacks belched black diesel smoke and the truck began to roll, tires crushing gravel. As the tanker moved away, Vince let out a slow breath and felt the tension begin to drain away. He doubted if the guy had heard anything, and what did it matter if he had? No one with any sense would want to get involved in their shitpull. Laughlin must’ve realized he had been caught listening in and decided to get while the getting was good.

By the time the eighteen-wheeler eased out onto the two-lane highway, Vince had already turned away, brushing through his crew and making for the diner. It was almost an hour before he saw the truck again.

Vince went to piss—his bladder had been killing him for going on thirty miles—and on his return he passed by the others, sitting in two booths. They were quiet, almost no sound from them at all, aside from the scrape of forks on plates and the clink of glasses being set down. Only Peaches was talking, and that was to himself. Peaches spoke in a whisper, and occasionally seemed to flinch, as if surrounded by a cloud of imaginary midges . . . a dismal, unsettling habit of his. The rest of them occupied their own interior spaces, not seeing each other, staring inwardly at who-knew-what instead. Some of them were probably seeing the bathroom after Roy Klowes finished chopping up the girl. Others might be remembering Clarke facedown in the dirt beyond the back door, his ass in the air and his pants full of shit and the steel-bladed shovel planted in his skull, the handle sticking in the air. And then there were probably a few wondering if they would be home in time for American Gladiators, and whether the lottery tickets they had bought yesterday were winners.

It had been different on the way down to see Clarke. Better. The Tribe had stopped just after sunup at a diner much like this, and while the mood had not been festive, there had been plenty of bullshit, and a certain amount of predictable yuks to go with the coffee and the doughn

uts. Doc had sat in one booth doing the crossword puzzle, others seated around him, looking over his shoulder and ribbing each other about what an honor it was to sit with a man of such education. Doc had done time, like most of the rest of them, and had a gold tooth in his mouth in place of the one that had been whacked out by a cop’s nightstick a few years before. But he wore bifocals, and had lean, almost patrician features, and read the paper, and knew things, like the capital of Kenya and the players in the War of the Roses. Roy Klowes took a sidelong look at Doc’s puzzle and said, “What I need is a crossword with questions about fixing bikes or cruising pussy. Like what’s a four-letter word for what I do to your momma, Doc? I could answer that one.”

Doc frowned. “I’d say ‘repulse,’ but that’s seven letters. So I guess my answer would have to be ‘gall.’”

“Gall?” Roy asked, scratching his head.

“That’s right. You gall her. Means you show up and she wants to spit.”

“Yeah and that’s what pisses me off about her. ’Cause I been trying to train her to swaller while I gall her.”

And the men just about fell off their stools laughing. They had been laughing just as hard the next booth over, where Peaches was trying to tell them about why he got his nuts clipped: “What sold me on it was when I saw that I’d only ever have to pay for one vasectomy . . . which is not something you can say about abortion. There’s theoretically no limit there. None. Every jizzwad is a potential budget buster. You don’t recognize that until you’ve had to pay for a couple of scrapes and begin to think there might be a better use for your money. Also, relationships aren’t ever the same after you’ve had to flush Junior down the toilet. They just aren’t. Voice of experience right here.” Peaches didn’t need jokes, he was funny enough just saying what was on his mind.

The Fireman

The Fireman Twittering From the Circus of the Dead

Twittering From the Circus of the Dead Nos4a2

Nos4a2 Horns

Horns Heart-Shaped Box

Heart-Shaped Box Thumbprint: A Story

Thumbprint: A Story Strange Weather

Strange Weather 20th Century Ghosts

20th Century Ghosts Full Throttle

Full Throttle At Home in the Dark

At Home in the Dark Thumbprint

Thumbprint Throttle

Throttle Throttle (Kindle Single)

Throttle (Kindle Single) The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2015

The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2015 Heart-Shaped Box with Bonus Material

Heart-Shaped Box with Bonus Material Horns: A Novel

Horns: A Novel